Author and scholar Dara pictured with Deborah Oleshansky, Director of the Jewish Community Relations Committee of the Jewish Federation of Greater Nashville

What is Judaism? How is antisemitism expressed in modern times? Does Holocaust education help combat antisemitism? Those are just a few of the topics author and scholar Dara Horn addressed when she visited Nashville last month. The latest in the Jewish Federation of Greater Nashville’s Shine a Light on Antisemitism series featured Horn’s discussion of her latest book, “People Love Dead Jews,” a series of essays that laments both the commercialization of Jewish tragedy, and the dearth of information about the vibrancy of Jewish culture as it is lived in today’s world. And while the book’s title is provocative, Horn said that is the point. “If the title makes you uncomfortable, what’s in the book will make you even more uncomfortable.”

Horn’s theory is that by reducing Jewish history to stories about the Holocaust, Anne Frank, and the destruction of Jewish communities throughout the ages, it ignores the deeper truths about Judaism and Jewish life. “Jews in non-Jewish societies often feel the need to erase themselves in order to make other people feel comfortable.”

The origin of the book stems from a request she received from National Geographic to write about Anne Frank. At first reluctant, she eventually decided to write the piece after learning about an employee of the Anne Frank Museum who was not allowed to wear his yarmulke during work. After a four-month deliberation, the museum’s board relented. “Four months is a really, really long time,” said Horn, “And the irony escaped them that they were basically forcing a Jew to hide his identity.”

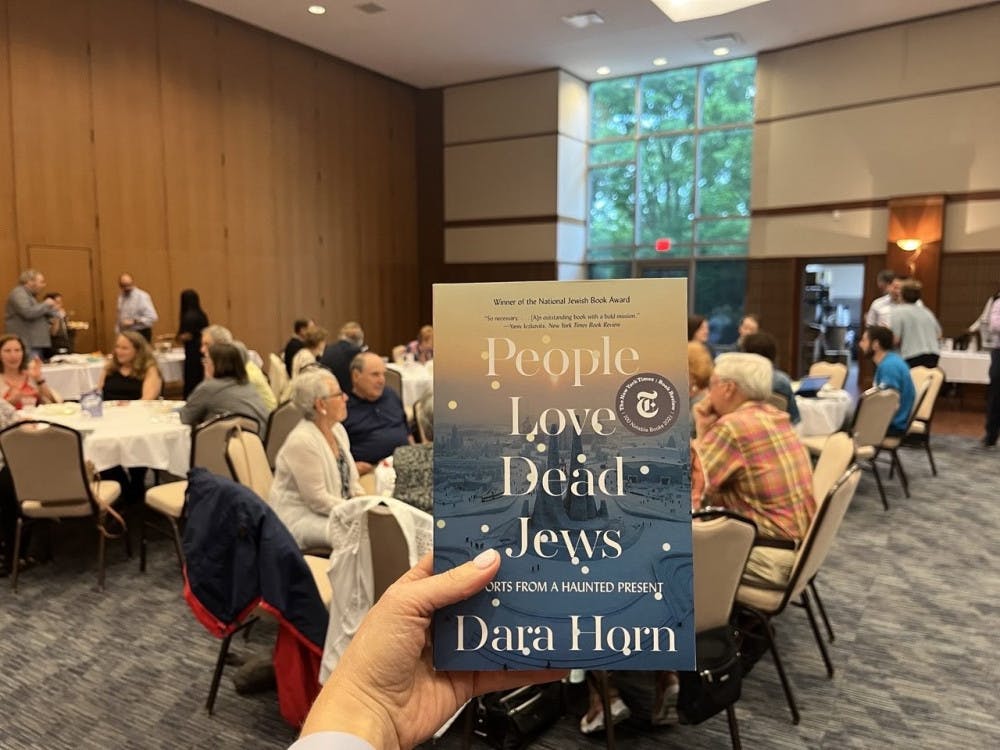

Attendees of the book club reception enjoyed light snacks and the opportunity to meet with Dara Horn.

The book works to dispel myths that she said also lead to the erasure of Jewish identity. She said family stories of names being changed at Ellis Island simply are not true. Immigrant names came from ship’s manifests and port of origin records, much like today. Horn said there is a different and very real story behind family name changes. “What we do have are court records of American Jews after the mass migrations of the ‘20s, ‘30s, ‘40s, and ‘50s going to court and changing their own names. And why were they changing their own names? Because of American antisemitism.”

The book’s essays are diverse but the thread that runs through them all is this idea of the lengths Jews go to fit into American culture and society. Attendee Amy Kammerman read the book following a recommendation by The Temple’s Rabbi Michael Danziger during Yom Kippur services. She said she found the book to be heavy, but also engaging. “She is so heartfelt. I would read an essay and just be pulled into it. The whole book is intense, but everyone can find something to relate to.”

In a recent article in The Atlantic, Horn wrote about her belief that Holocaust education does little to combat antisemitism. “There is no data to support the idea that it does, and it [Holocaust education] has been going on for 50 years.” She said her approach was probably not what The Atlantic editors were expecting, “I know it made them uncomfortable, but at least we started the conversation.”

Dara Horn spoke at The Temple about her latest book “People Love Dead Jews.”

It is this notion of discomfort that drove much of the discussion. When it comes to teaching about Judaism, she says the answer is built into the tradition. “What about looking at Shabbat as a way to combat antisemitism? Think of it as a political initiative, a form of social justice.” She said that inviting someone into the home to share a Shabbat meal or a Passover seder provides real life experiences and insights into Jewish life and community. “How about look at the seder as a liberation story and invite the Black community to participate.”

Attendees were inspired by Horn’s perspective and her ability to articulate what some people only think about. Heidi Allen said she was moved by Horn’s depth of knowledge of Jewish history, and her ability to articulate her ideas. “She made it accessible. I started this conversation as a scared little girl in South Carolina just wanting to fit in with everyone else. But I truly looked at things a different way after reading her book.”

Horn’s focus on the uncomfortable realities of the American Jewish experience is one that for some attendees was unexpected. Teen Cohen said, “She brings such a unique perspective to our collective history. I like the angles from which she approaches the conversation.” Cohen also appreciated Horn’s views on Holocaust education. “She shared her perspective so well and wove in her ideas related to Holocaust education, its strengths and weaknesses.”

Horn expressed her difficulty in addressing the responses from Jewish readers who want to share their own experiences with antisemitism. “It’s like this horror story litany. And the stories they’re sharing with me are not the kind of things that would end up in an ADL [Anti-defamation League] report.” She goes on to relay incidents such as people’s treatment by their mother-in-law, their employer, their boyfriend. As she calls them, private moments, that cannot be written about but cut deeply into the psyche of the Jews who experience it. “There are ways people compartmentalize these things to make excuses for it. The political piece is one of those ways, there are other ways people do it, and that is simply one of those.”

The message of the evening was not completely a dark one, however. The final question asked came from a parent of young children wanting to know how to instill a strong Jewish identity in the midst of a predominantly Christian world. Horn said the answer lies in Jewish tradition itself.

“The tradition is set up with the expectation that you’re going to be living in a non-Jewish society,” she said. “Your child is going to experience Shabbat, there’s a day where they’re not doing homework or school work…that child will hopefully in one form, or another be studying Torah. The Torah is the story of defeat after defeat after defeat, but it is also one of resilience after resilience after resilience…That child will be celebrating holidays like Passover, where they’re going to be telling stories of national liberation…They’re going to see that they’re part of this enormous 3,000 year old chain of learning what it means to be human, learning what it means to be part of a counterculture.” In short, she says, children who live a Jewish life, in whatever form their family takes, will be getting what she calls a master class in living in a pluralistic society. “When you give a child that gift, that child really is prepared.”

The Jewish Observer is published by The Jewish Federation of Greater Nashville and made possible by funds raised in the Jewish Federation Annual Campaign. Become a supporter today.