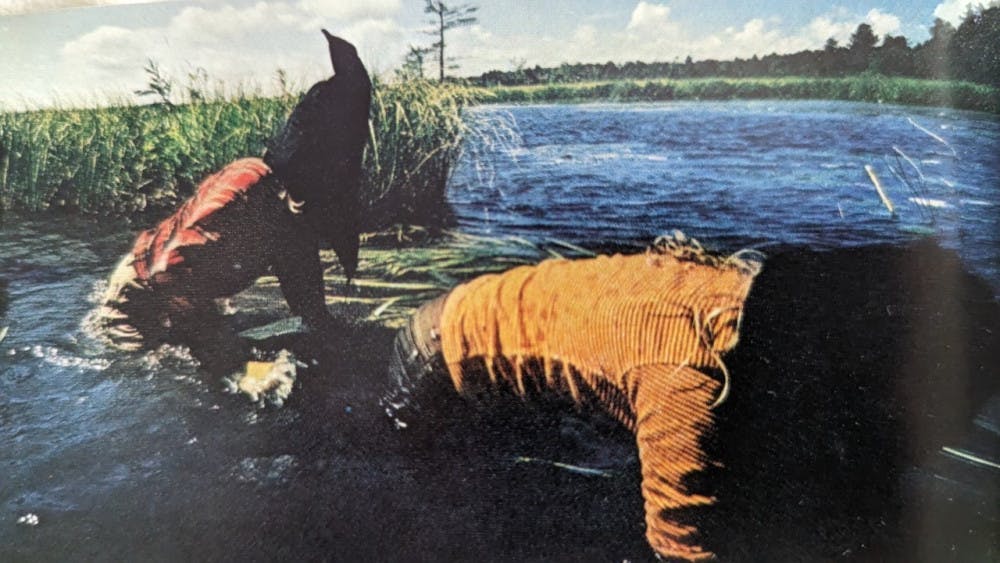

Melissa Sostrin, r, as a child, participated in a unique nature program at summer camp. Photo courtesy of National Geographic.

I think I raised my sons right: on Mother’s Day one of them called and wished me a “Happy Hallmark holiday.” I know, I know, the holiday preceded the company by a few years. However, I’ve downplayed the calendar event telling them we could celebrate all year if they honored and loved me the other 364 days. I often think of my mother, and not just on Mother’s Day and what a profound effect she had on my love of nature.

The first time she went to camp she dropped and rolled with abandon in the grass, and when the director asked what she was doing she replied that her mother never let her get dirty. And so, we were allowed to get dirty, to play for hours in the empty lot next door, and often, fortunately, farther afield.

The camp I attended when I was 10 had a radical, for that time, nature program. Instead of a typical program of bug and flower collecting and learning then forgetting their names, its aim was for campers to become part of nature. In the photo from the National Geographic story about it, we were hooded to heighten our sense of touch, and crawled through the shallows of a lake bottom pretending to be raccoons searching for food. I’m that first camper and still have awe for raccoons, the state mammal of Tennessee. Their highly specialized front paws have hairs that enable them to find and identify what they touch and are more sensitive when wet more easily.

In William Blake’s poem, “Auguries of Innocence” he begins,

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

The first time I held infinity I was about nine years old. It was a cool, early morning as I walked to observe an ornithologist and his helpers catching and banding birds at the place we were vacationing. I saw a hummingbird alighting on flowers and because of the cold, it was moving much slower than the average 61 miles per hour. I reached out and gently closed my hands around it, feeling its fluttering as I carried it to be banded. Decades later I still thrill to the sight of hummingbirds in my yard.

There are eight hummingbird species in Tennessee, and you can attract them with a feeder, or more naturally, by planting native jewel weed or trumpet creepers or perennials such as purple cone flowers and bee balm. They also feed on insects so minimizing pesticide use would be good for the birds and the earth. For more information, check out the University of Tennessee Cooperative Extension Service document on hummingbird gardening.

One of the young people banding birds that day was Michael Fay, a biology student at the University of Arizona. My mom invited him to accompany us on a camping trip to Alaska, and bravely, he said yes

to a summer with six kids ages 11 to three, and my mom. I’d like to think that those weeks in the wild, including a bear sighting along the Teklanika River (when Michael tucked my youngest brother under his arm like a football and ran) contributed to his career as a passionate conservationist. He has spent most of the last few decades in Africa completing a mega-transect and running national parks in Gabon. My brother attended a speaking event when Fay was state side some years ago and introduced himself. He said, “Your mother was a wild woman,” which is somewhat accurate and a beautiful compliment to her.

My mother found holiness in the world around her and took photos of flowers and mushrooms, and mountains and sunsets, to remind her what was out there when she was back in suburbia running for the school board, chauffeuring us around, making dinner or doing any one of a thousand mundane tasks. While many of us can’t travel or don’t have the time or resources, we can find the beauty of nature in our own backyard. Rachel Bluwstein, considered the founding mother of modern Hebrew poetry did, and wrote about it in the poem “Pear Tree.”

Spring had a hand in this: a person wakes up

and through the window he sees

a flowering pear tree

and all at once this mountain that weighed on his heart

crumbles and ceases to be.

The Jewish Observer is published by The Jewish Federation of Greater Nashville and made possible by funds raised in the Jewish Federation Annual Campaign. Become a supporter today.